Not a member yet? Sign Up!

Info

Please use real email address to activate your registration

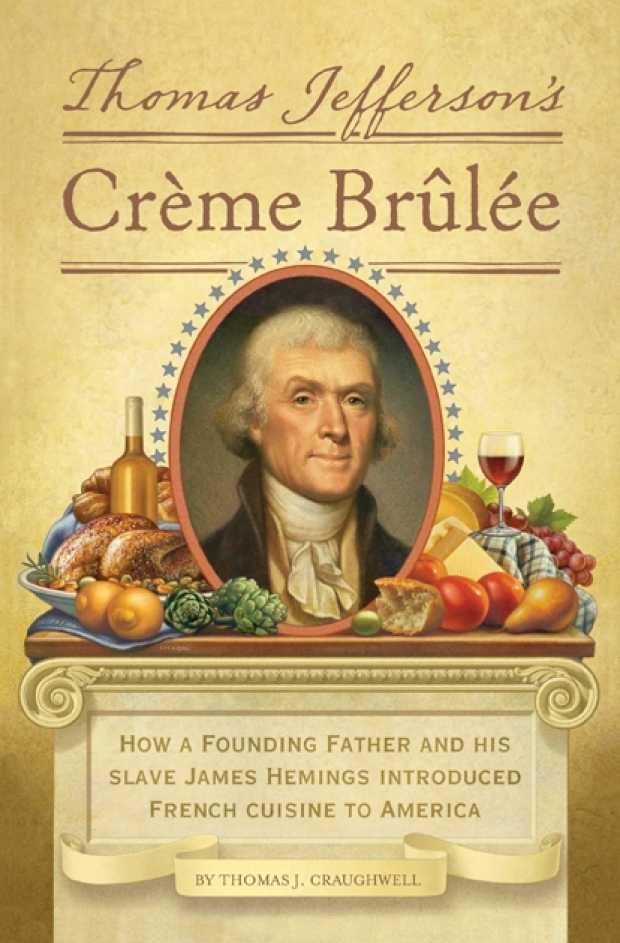

“If Thomas Jefferson were a celebrity chef, he would be Iron Chef Masaharu Morimoto. A perfectionist with food that had to be fresh and in season, delicious and visually appealing,” says Thomas J. Croughwell the author of Thomas Jefferson’s Crème Brûlée. How a Founding Father and His Slave James Hemings Introduced French Cuisine to America.

I read this book as The Kitchen Reader August 2014 choice and for The Foodies Read 2014 Challenge.

Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence served two terms as the third President of the United States (1801-1809). He lived in France from 1784-1789 first as trade commissioner then as minister.

Jefferson is well known as a public official, historian, philosopher, plantation owner, and an enthusiastic gardener. However, Croughwell writes, Jefferson was also a serious gourmand.

Published by Quirk Books, Thomas Jefferson’s Crème Brûlée is an engaging 256-page book with US and French History, fine dining, and classic recipes.

In the first page of the Prologue, The Man Who Abjured His Native Victuals, the author sets the course of the book with a note Jefferson wrote to his friend before leaving for Paris from his home in Monticello Estate, Virginia.

“I propose for a particular purpose to carry my servant Jame with me,” Jame was 19 year old James Hemings, and the particular purpose was to have James trained by some of the finest chefs in France, eventually in exchange for his freedom.

Chapter 1 of the book, Americans in Paris, is an account of Jefferson’s trip to Paris, about his fellow Americans, and the first apprenticeship for Hemings with Combeaux, a restaurateur who has a catering business.

A Free City, Chapter 2, illustrates how Jefferson is very fond of Paris. “A Walk about Paris, according to Jefferson, will provide lessons in history, beauty and in the point of Life. James Hemings spent most of his time as a culinary apprentice and servant of Jefferson, an American diplomat.

Several pages in Chapter 3, A Feast for the Palate, tells the story about Madame de Pompadour, the official mistress of Louis XV who was a good cook that encouraged royals and nobles prepared meals for intimate dinner parties. Madame du Barry, the next mistress, initiated light flavorful dishes that left guests satisfied with the taste without feeling bloated. Examples of these kinds of dishes are poached chicken in a cream and butter sauce, and roasted chicken with watercress salad.

James Hemings learned the French way of choosing quality ingredients, preparing and serving food in impressive presentations.

Chapter 4, The Wine Collector and Rice Smuggler, details Jefferson’s twenty-four hundred miles round trip from Paris to Marseilles, passing the Alps, traveling to northern Italy and back to Paris that he took for several months.

In what he called a grand tour, Jefferson investigated “architecture, painting, sculpture, antiquities, agriculture and the condition of the laboring poor.” He visited Champagne, Burgundy, Rhone-Alpes, Languedoc-Rousillon, and Provence and learned about wine production.

Jefferson was interested in commodities that might be cultivated in America such as figs, seedless grapes, capers, pistachios, almonds and rice.

Brother and Sister, Reunited, the title of Chapter 5, is a story about Sally, James Heming’s sister who arrived in Paris to accompany Jefferson’s daughter. At that time James was apprenticing under the executive chef for the Prince of Conde.

In addition to culinary skills, an executive chef, or a chef de cuisine, should also master managerial skills.

Chapter 6, Boiling Point, is about the traumatic French Revolution that Jefferson witnessed. He was ready to leave France for a new responsibility in his country.

Jefferson sent home to Monticello 86 crates of kitchen utensils and equipment, wines, cheeses, olive oil and mustard as well as seedlings of fruit trees and ornamental tree.

The Art of the Meal, Chapter 7, is the final chapter that depicts homecoming in Monticello, Virginia. Offered a position as The Secretary of State (1790 -1793) based in New York, Jefferson brought James Henning with him to be chef de cuisine.

Jefferson then instructed James to train his brother, Peter Hemings, on the Art of French Cooking. James Hemings who became a free man in 1795 made an inventory of kitchen equipment at Monticello that include French copper pots and pans, and brass and marble pestles and mortals.

Jefferson became Vice President under President John Adams his fellow American in Paris, and was eventually elected as President in 1801.

He invited Hemings to become his chef at the President’s House but no deal came through although James did return to Monticello to serve as chef during Jefferson’s long vacation from Washington.

The book did not have a happy ending as Hemings died at the age of 36.

As President, Jefferson employed French Chefs: Joseph Rapin, Honoré Julien, and Étienne Lemaire.

He has learned in France that fine food and fine wine combined with lively conversation could serve a political purpose.

In the last page of the Epilogue, Craughwell reasons that Julia Child, an American famous for her book Mastering the Art of French Cooking, was not the person who introduced Americans to French Food. The real credit should go to Thomas Jefferson and James Hemings.

----------------------------

Images: Quirk Books/Book Cover, Crème Brûlée Recipe; 123rf/Steve Estvanik: Monticello; Free Artist: Paris; Brent HPfacker: Crème Brûlée; Patricia Hofmeester: Pots & Pans.